Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on Canvas 47.6 x 48.3 cm

Oil on Canvas 47.6 x 48.3 cm

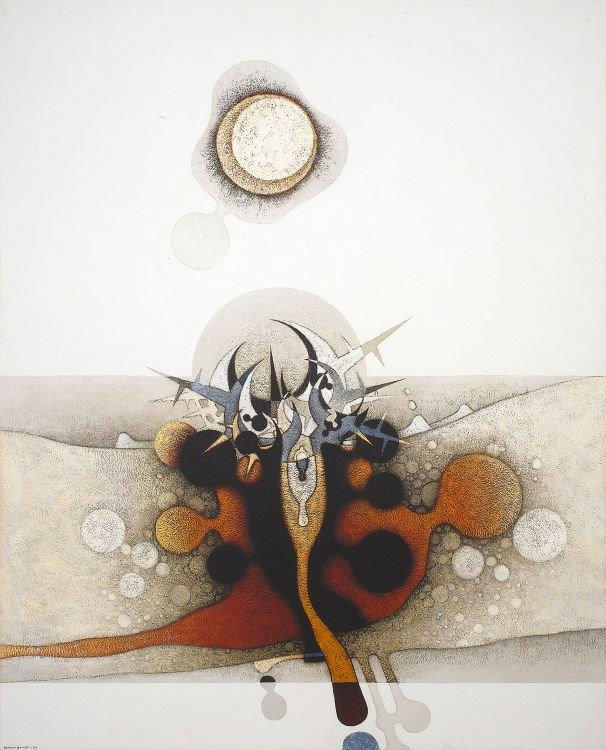

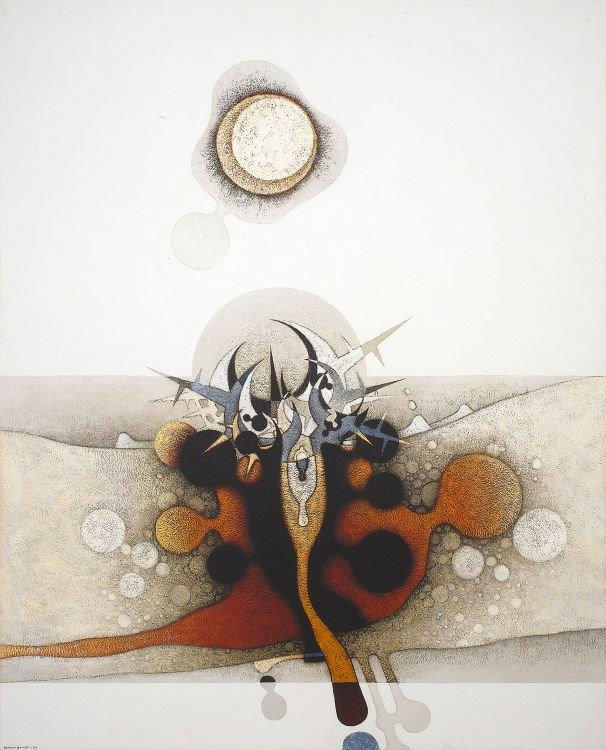

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

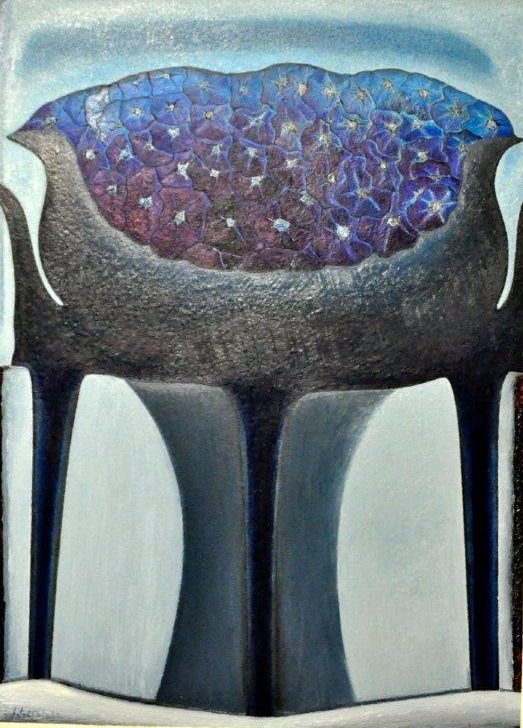

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Dated 1996 Signed lower right, Titled and dated verso, Unframed

Northwest Coast

Inuit Sculpture Artist Unknown

Sedna Soapstone

Sedna Soapstone

High Fired Pottery 27.5 cm x 18.7 cm x 18.7 cm

Acrylic Painted Skull 44 cm x 20 cm

Oil on canvas Signed; Numbered 12-06 76 x 58 cm

Oil on canvas Signed; Numbered 12-06 76 x 58 cm

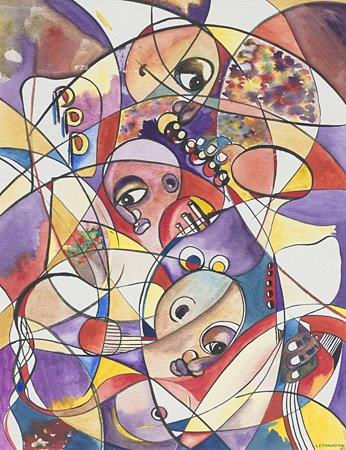

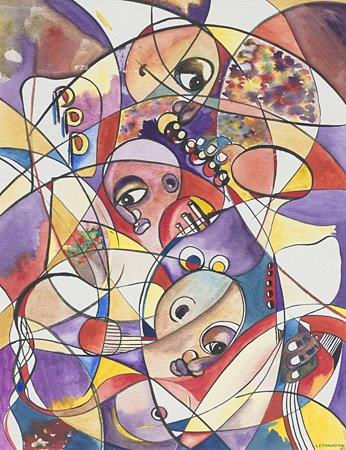

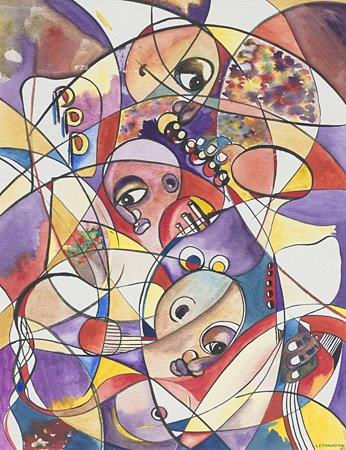

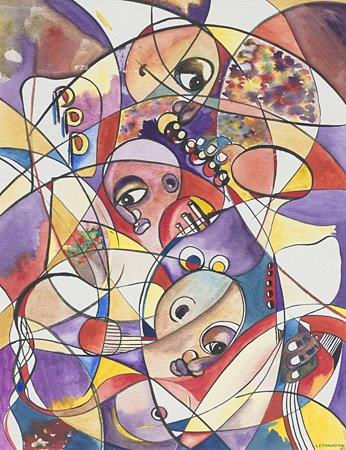

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Oil on canvas 57.2 x 85.5 cm

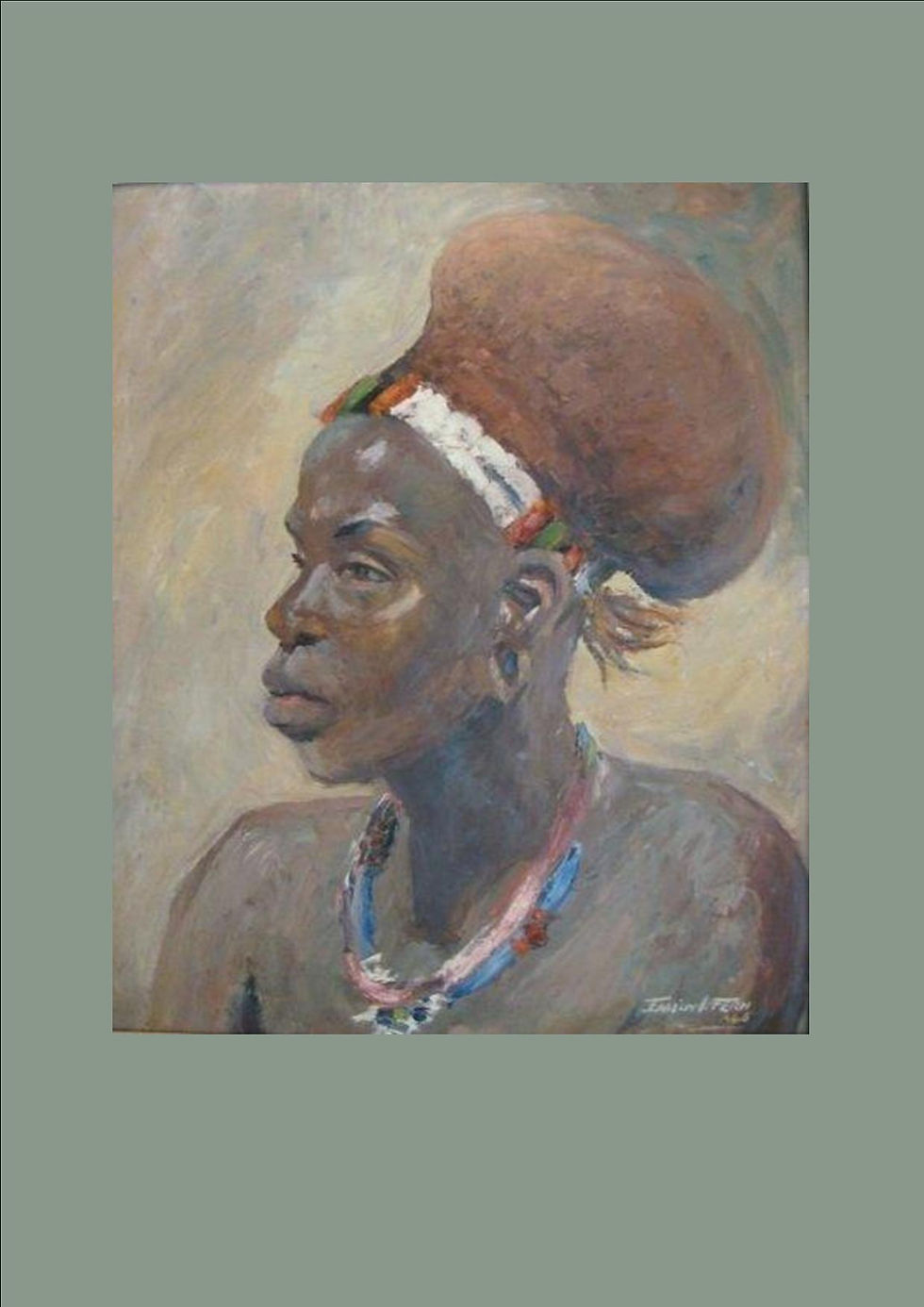

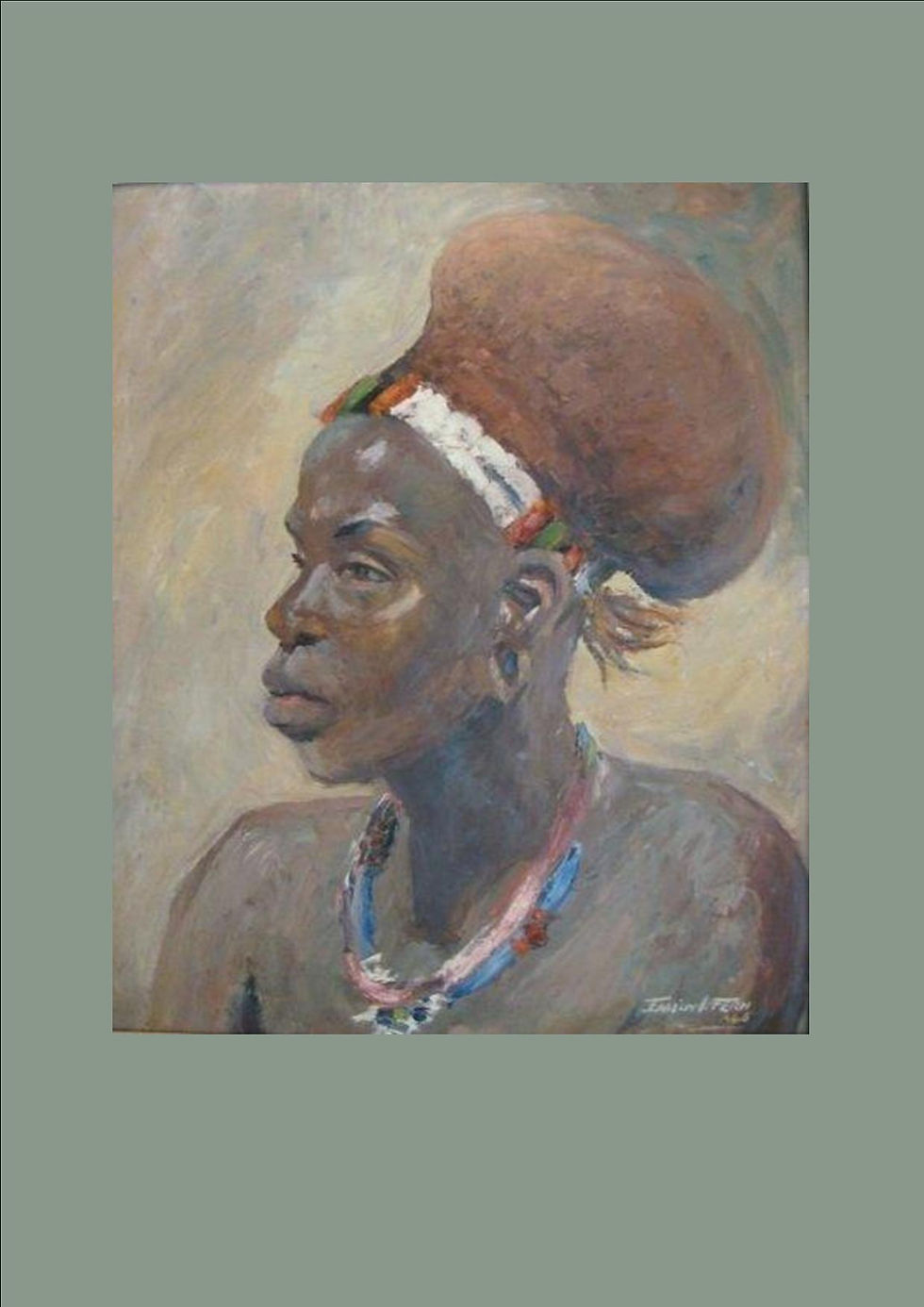

Oil on Board Signed Dated 1962 90 cm x 65 cm

Oil on Board Signed Dated 1962 90 cm x 65 cm

Coloured pencil on paper 24.1 x 18.4 cm 2015

Sunburst Mixed Media on Board 122.5 x 99 cm

Sunburst Mixed Media on Board 122.5 x 99 cm

Bobbie Burgers

Bobbie Burgers is a contemporary Canadian painter. Her lush and Expressionistic depictions of flowers teeter on the verge of abstraction, bursting with bright color and laden with thickly applied, textural paint. “Flowers, to me, are the opposite of still,” the artist has explained. “Changing from minute to minute, they are perfect symbols for life, death, yearning, and beauty. My brushstrokes are layered with my own internal charges, depicting anger, frustration, softness, wanting, and more.” Born in 1973 in Vancouver, Canada, she studied Art History at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. Her work has been exhibited widely at home and abroad, notably including Art Market San Francisco and Equinox Gallery. Today, her works are in the collections of the Berost Corporation in Toronto and the Royal Bank of Canada, among others. Burgers lives and works in Vancouver, Canada.

Bobbie Burgers

Bobbie Burgers is a contemporary Canadian painter. Her lush and Expressionistic depictions of flowers teeter on the verge of abstraction, bursting with bright color and laden with thickly applied, textural paint. “Flowers, to me, are the opposite of still,” the artist has explained. “Changing from minute to minute, they are perfect symbols for life, death, yearning, and beauty. My brushstrokes are layered with my own internal charges, depicting anger, frustration, softness, wanting, and more.” Born in 1973 in Vancouver, Canada, she studied Art History at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. Her work has been exhibited widely at home and abroad, notably including Art Market San Francisco and Equinox Gallery. Today, her works are in the collections of the Berost Corporation in Toronto and the Royal Bank of Canada, among others. Burgers lives and works in Vancouver, Canada.

Oil on canvas Signed 32 x 39 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 32 x 39 cm

Oil on board 44 cm x 45 cm

Oil on board 44 cm x 45 cm

Oil on Canvas Dated 2012 75 cm x 57cm

Oil on Canvas Dated 2012 75 cm x 57cm

Oil Signed .Titled 88 x 120 cm

Oil Signed .Titled 88 x 120 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Acrylic on Board Signed 44 cm x 40 cm

Acrylic on Board Signed 44 cm x 40 cm

Colour Pencil on Paper Signed 16 cm x 11 cm

High Fired Pottery 27.5 cm x 18.7 cm x 18.7 cm

Signed Oil 24 cm x 35 cm

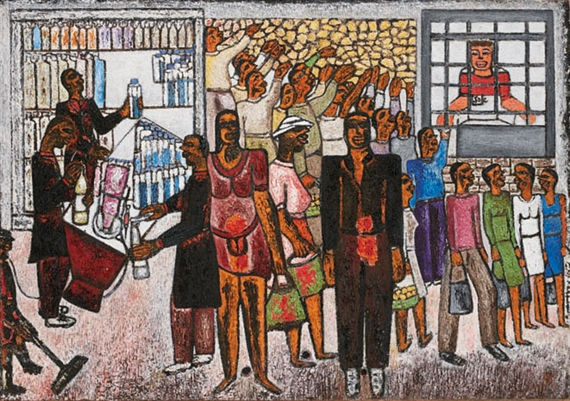

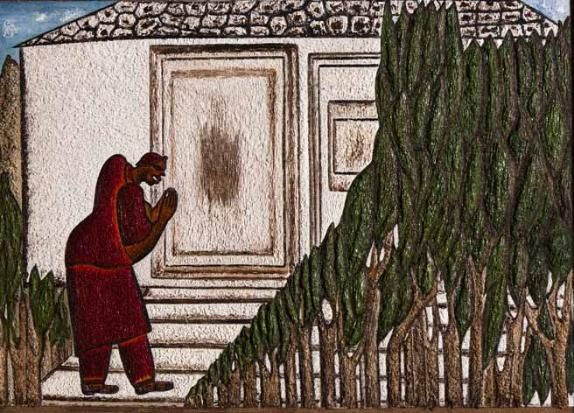

Contemporary South African Art

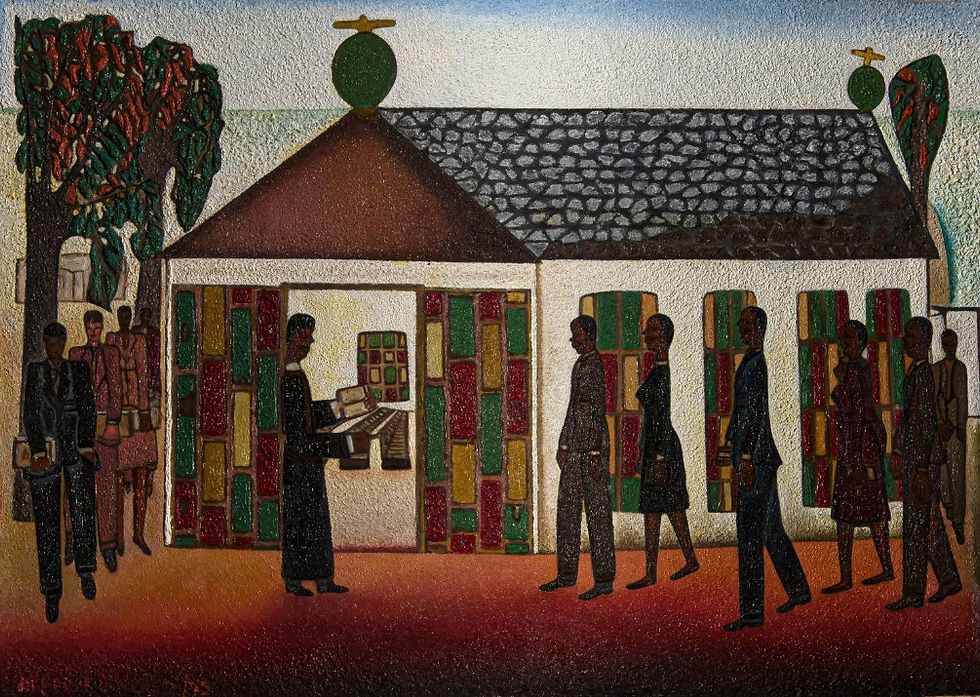

Thoba, Alfred

Born 1951, Johannesburg (Sophiatown)

During the apartheid era, Alfred Thoba was

living illegally in a small garage in Johannesburg, painting at night with the aid of a paraffin lamp. He was forced to transport his paintings from hiding place to hiding place, in fear of the police uncovering his politically-charged work. Following the Soweto Riots of 1976 –

a subject that inspired one of Thoba’s best-known and most controversial paintings – artists decided it was time they contributed more actively to the condemnation of the violence ravaging their country. This resolve inspired

a movement now referred to as Resistance

Art, and Thoba was one of its most active proponents. Thoba’s 1976 Riots was exhibited at Johannesburg’s Market Gallery in January

of 1988, as part of the 100 Artists Protest Detention Without Trial Exhibition. The show was subsequently raided by the police, and Thoba’s work was photographed for their files. Thoba’s paintbrush not only condemned white-on-black violence, but also brought to light the effects of apartheid amongst blacks themselves. In the painting She was Murdered in a Crowd,

a woman is killed by members of her own community after being accused a traitor to the liberation cause. Years of political engagement through art brought fruitful results: in the now famous work Thank you Mr. FW de Klerk for Handing Over South Africa to Nelson Mandela, Thoba rests his case.

In post-apartheid South Africa, Thoba remains moved by the plight of the people in the black townships: not so much the violence as the effects of urbanization and westernization on traditional values. Frequent subjects include kids who have turned to stealing, prostitution and violence to survive on the streets. Human relationships and personal suffering also serve as inspiration, as do contemporary events, which Thoba draws from newspaper articles.

In either case, humanity is central to Thoba’s work, resulting in paintings charged with emotion.

Thoba did not receive any formal art training, and the only exposure to art came through his grandfather, who made pots for the family. Thoba paints in a "naïve" style not unlike that of Henri Rousseau, applying thick coats of acrylic paint onto board, and shaping his figures in a stylized and stiff manner.

Thoba was nominated for the prestigious Vita Art Now Awards in both 1992 and 1994. He has exhibited in New York, Washington, Chicago and Toronto, while one of his exhibitions was sent on a year-long tour to Germany.

Oil on pPper 58 cm x 77 cm

Signed 52 cm x74 cm

Oil on Board Signed 59 cm x 81 cm

Oil on Canvas on Board Signed (verso) Alfred Thoba 1-11-2011 37.5 cm x 47 cm

Oil on Board Signed 76 cm x 56 cm

Oil on Paper 65 cm x 50 cm

Oil on Board Signed & Dated 2017 58 cm x 81 cm

Oil Pastel and Chalk Pastel on Paper 62 cm x 70 cm

Oil Signed and Titled Verso 58 cm x 80 cm

Oil on Paper Signed 77 cm x 57 cm

Oil on Board Signed and Dated 91 Title on Reverse 53 cm x 58 cm

Oil on Canvas Laid Down Signed & Dated 2009 on the Reverse 30 cm x 40 cm

Oil on Board Signed and Dated 30-5-2009 on the Reverse 30.5 cm x 41.5 cm

Oil on Canvas Laid Down on Board Signed Dated 20-8-2015 on reverse 48 cm x 58 cm

Signed Enamel on Paper Indistinctly Dated 47 cm x 67 cm

Oil Pastel on Paper Signed & Dated Inscribed Title Reverse 49.5 cm x 72 cm

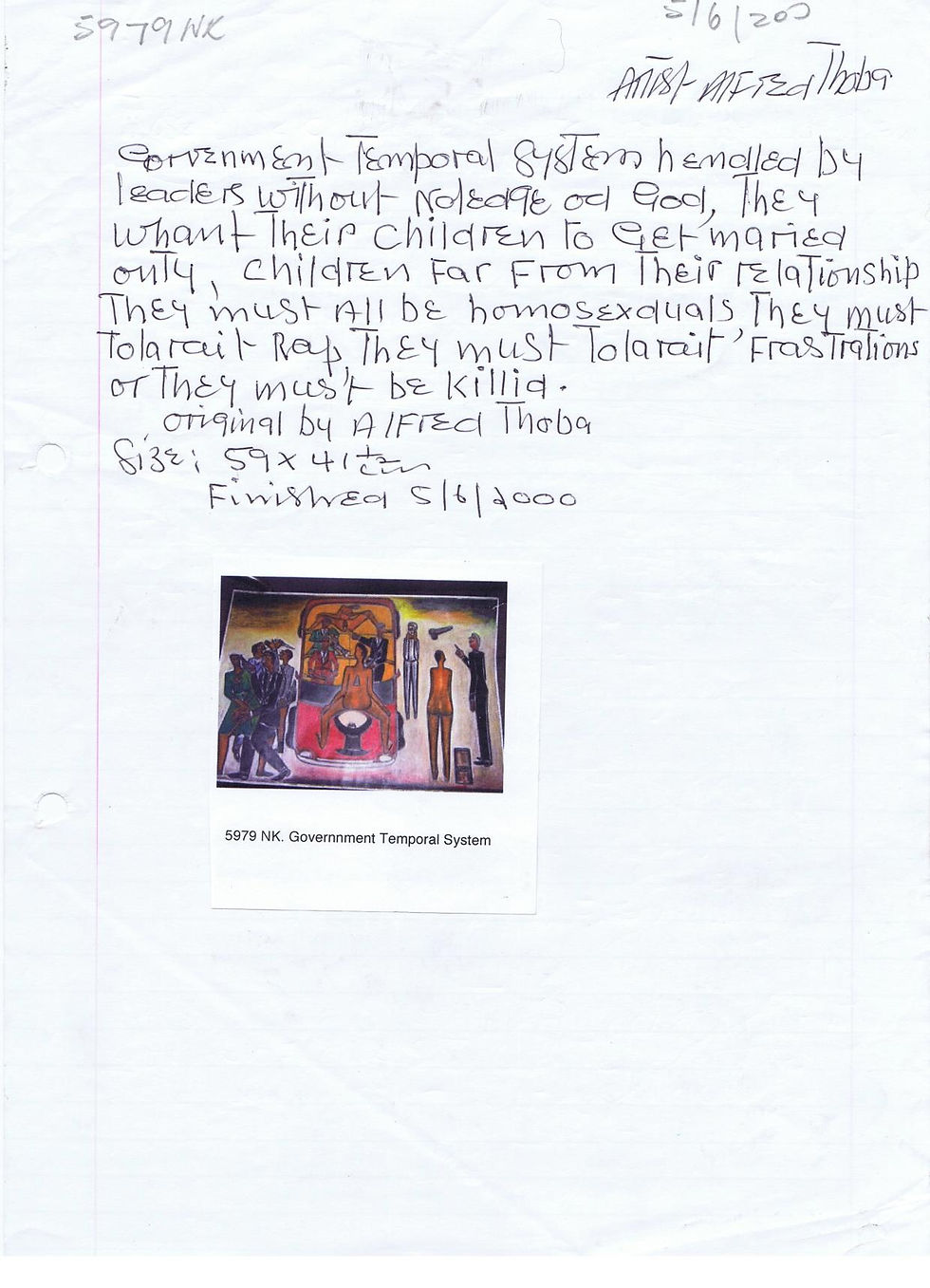

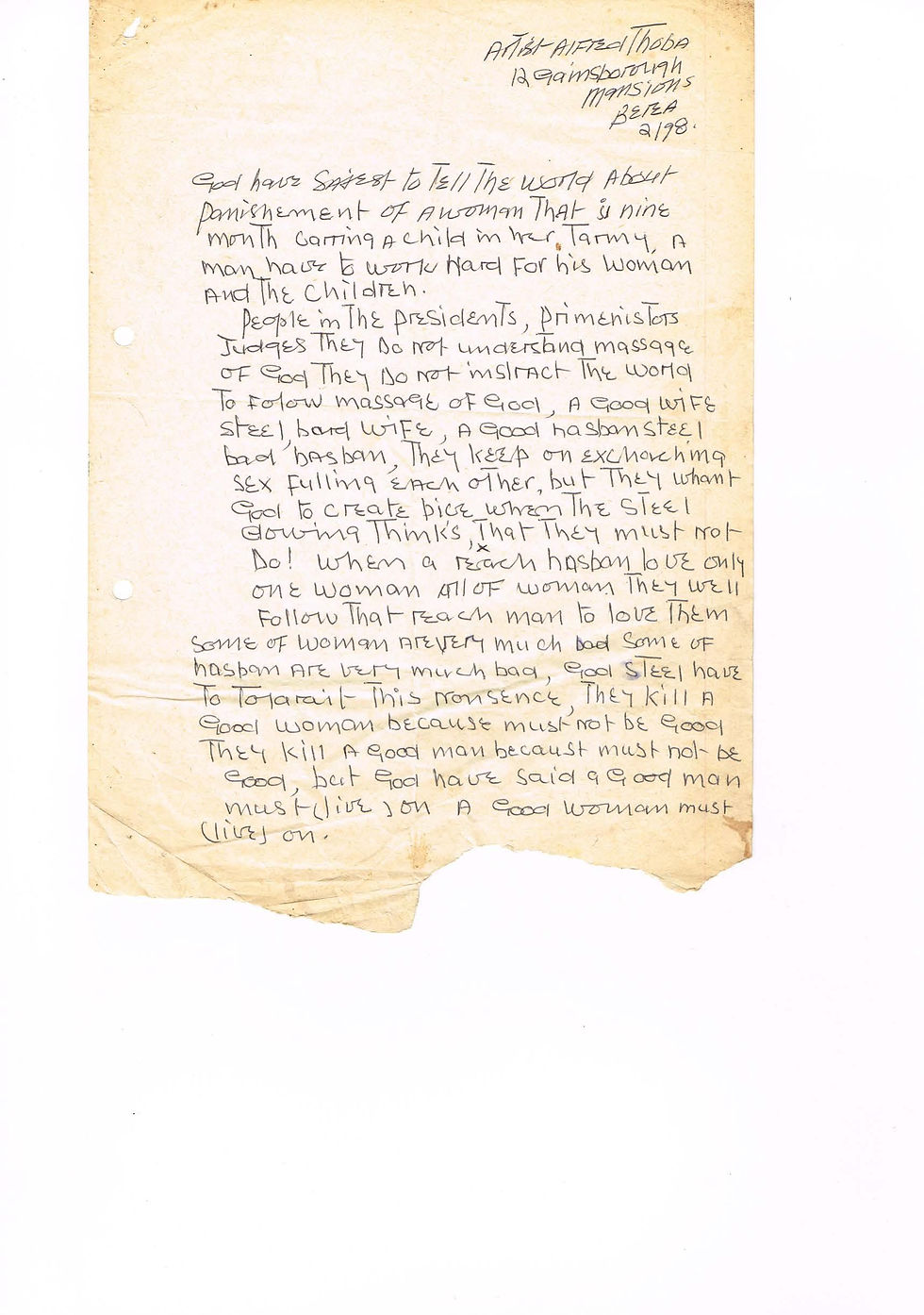

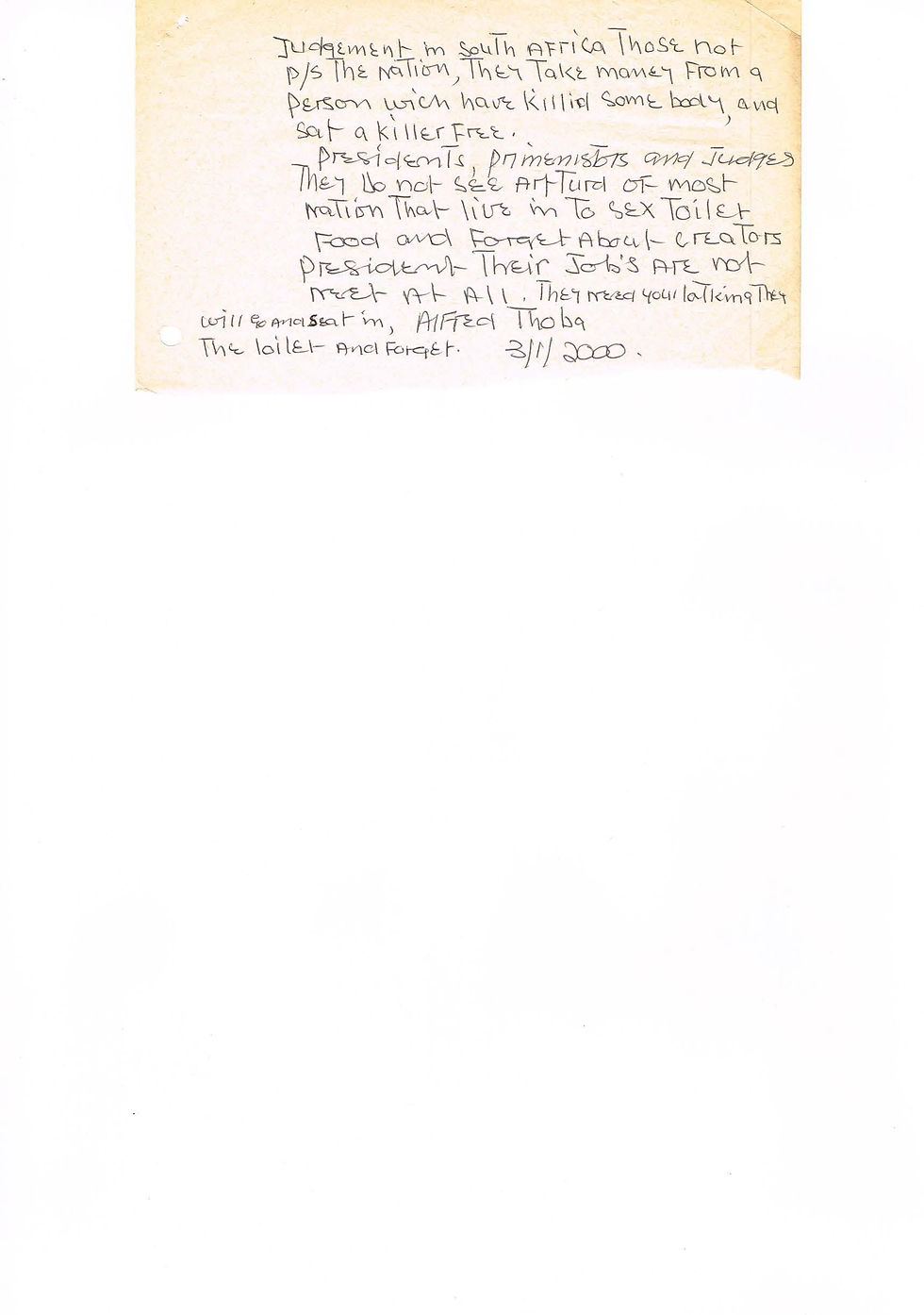

Handwritten Letter

Handwritten Letter

Mother and Child Meal Time Letter

Oil on Canvas, Laid down on Board Signed 46.5 cm x 56.5 cm

Oil on Board Signed 46 cm x 57 cm

Oil on Board Signed and Dated '87 60 cm x 80 cm

Peace to South African Married Women

Handwritten Letter - Page 2

Describe your image here

Handwritten Letter - Page 1

Describe your image here

Describe your image here

Oil on Paper Signed 48.4 x 66 cm

Alfred Thoba - Tokolosh Letter

Handwritten Letter - Page 1

Handwritten Letter - Page 2

Describe your image here

Handwritten - Pre-Painting Letter - Page 1

Oil on paper 64 cm x 47 cm

Oil on Board Signed and Dated 3-3-20 50 cm x 70 cm

Oil on Canvas Laid on Board Signed 20-7-2009 43 cm x 53 cm

Hand Written Letter

Handwritten Letter

Letter Description

ZCC Zaon Church Have Evil Attitude of Killing Beautiful People Because of Jealousy Oil on Board - Mixed Media Signed 36.5 cm x 63.5 cm

ZCC Zaon Chuch - Written Note by Alfred Thoba

Describe your image here

Oil on Paper 1994 58 x 77 cm

Oil on Paper 58 cm x 78 cm

Oil on Paper 63.5 cm x 41 cm

Describe your image here

Pastel on Paper Signed 59 cm x 43 cm

Oil Signed Inscribed Verso 58 x 76 cm

Oil Signed Verso 70 cm x 34 cm

Oil Signed Verso 70 cm x 34 cm

Handwritten - Pre-Painting Letter

Handwritten - Pre-Painting - Letter - Page 2

Oil on Paper Laid Down On Board Signed and Dated 95 61 cm x 86.5 cm

Oil on Paper Laid Down On Board Signed and Dated 11.1.96 85 cm x 77 cm

NOTES

The category of ‘Outsider Art’ has received much mainstream attention in the last few years, including Lynne Cook’s curation of Outliers and American Vanguard Art (2018) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and then a year later, the first auction of “Outside and Vernacular Art” by Christie’s New York in 2019 (and followed annually since then by sales in the Outsider Art category). Such is the extent of its mainstreaming that even Christie’s own publicity for their auctions invokes the “master” narrative, characterising the work as “masterpieces” and the artists as “self-taught masters”.1

In its reach, which is neither easy nor simple, ‘Outsider Art’ (and its precursor, ‘Art Brut’) is seen to include artists who are not formally trained, who are ‘outside’ the mainstream artworld, who create elaborate fantasy worlds, and/or who have a mental illness. While it is not a style, the use of ‘naïve’ often gets pushed in the face of Outsider Art, and especially in auction sales it often sits in proximity to traditional ‘African’ and ‘Oceanic’ art, as well as ‘folk’ art, with certain implications for what they are understood to share.

At face value, Alfred Thoba fits many of the criteria used to characterise ‘Outside Art’. He has no formal training as an artist, with his singular early approach to Bill Ainslie for lessons rebuffed by the latter because he thought Thoba had a ‘natural’ talent.2 In Thoba’s own characterisation of the encounter, “I went to them [Ainslie] with [my emphasis] the knowledge; I was actually born with it”.3 There are no apparent art historical references in Thoba’s work, and in interviews I conducted with him, he never once mentioned another artist of his own accord.

This disregard for other art and the art histories that surround them is less about a disparaging of other artists as it is about Thoba’s own understanding of the role of painting as a convenient medium, not only to release the messages that thicken and congeal inside his head, but also to travel these messages into public. The vitality of these messages is reiterated in the letters that accompany Thoba’s paintings, earnestly written to ensure that whoever buys the painting properly understands its meaning. Oftentimes Thoba seems genuinely unconcerned with the currency of his paintings as art objects, or the place of his paintings in an art historical tradition or canon. Instead, the significance of a sale is as much about the successful transmission of a message as it is about the financial gain. This world constituted by Thoba’s messages is a complex fantasy of autobiography, readings, obsessions, trickery, cosmologies, dreams, visions, and morality. While they are highly personal, and often autobiographical, Thoba himself very rarely appears in his own paintings.

Thoba’s painterly technique has little academic reference and is instead derived from the release he experiences through the unique process of the thickly applied paint, carefully built up into areas of relief and teased into peaks using with a variety of tools. It is obsessive, time-consuming work, and the quality of his attention to detail is clearly reflected in the intricacies and nuances of the finely teased paint.

Thoba has fallen in and out with many of the prominent dealers and galleries in South Africa. It created a consequent pattern of him moving in and out of the artworld, but ultimately contributing to a sense of what oftentimes feels like an outsider status. Mention his name inside the mainstream artworld and the response is either a blank stare, or a sketchy reference to his 1976 Riots painting that was shown at the Detention Without Trial: 100 Artists Protest exhibition in 1988, and reproduced in Sue Williamson’s book, Resistance Art in South Africa (1989), then disappeared for more than 20 years before being sold at Strauss and Co for close to R1 million in 2012.4

Why isn’t ‘Outsider Art’ a more feted category here and why isn’t Thoba celebrated as a significant artist in this categorical formulation? Mostly because there are more significant flaws in the category, not least of which is its intersection apartheid history. The most obvious flaw with ‘Outsider Art’ is the normative assumptions it makes in framing the category, notably in terms of what is understood as ‘normal’ (and thereby inside). ‘Outsider Art’ reads as a litany of negatives, and of what is not.

The second flaw is that ‘Outsider Art’ adopts a static understanding of makers within the category, a failing that is most obviously exposed when outsider artists become part of major museum collections. This schizophrenic parallel habitation of outside but inside is an ambivalence easily tolerated by the mainstream art world.

But it is the third flaw in the understanding of ‘Outsider Art’ that is most relevant especially in the South African context, and this is the extent to which the category is complicated by colonial and apartheid histories that deliberately prejudiced black artists in terms of not only formal art education (and where such education was available, it was often patronising and infantilising) but also access to a mainstream ‘white’ artworld. Black artists were forced into living and working conditions that made their personhood and practice separate, and outside. Even in the United States, the prominent outsider artists are African-American – such as William Edmondson and Bill Traylor, both of whose parents were slaves, and whose work now commands the highest prices at auction in the ‘Outsider Art’ category –underscoring the parallel intersections of

the category and racial prejudice.

When Jean Dubuffet coined the original term ‘Art Brut’ (subsequently and largely replaced by ‘Outsider Art’), it was a definition against the ‘mimicry’ and ‘clichés’ of mainstream and established art. The critical value of the ‘Outsider Art’ category, in spite of its assumptions and flaws, is the way in which it brings attention to the tidy intellectual formulations of art history and the rigid structures of the established artworld. If Thoba is uninterested in art history, how do we constitute art history’s interest in Thoba’s work? The awkwardness of ‘Outsider Art’ in the South African context is exactly it’s value in being an important signal that South African art history needs reimagination, and that the traditional distinctions in time and place, habitually used to understand South African art, don’t work to comprehend the significance and importance of Thoba’s oeuvre within local and international contexts.

—Rory Bester, 2022

1. See ‘Christie’s New York Presents Outsider Art’, 19 January 2022. Source: https://www.christies.com/about-us/press-archive/details?PressReleaseID=10344&lid=1.

2. Per communication with Gail Behrmann, 2018.

3. In Rina Minervini (1990) ‘Thoba: Tolerating art with love’, Sunday Star (Review section), 4 February, page 10.

4. See https://www.straussart.co.za/auctions/lot/11-jun-2012/409.

PROVENANCE

Warren Siebrits Fine Art, Johannesburg, 30 May 2006.

The Oliver Powell and Timely Investments Trust Collection.

EXHIBITED

Wits Art Museum, Johannesburg, Alfred Thoba: A Step Becomes a Statement, 13 March to 3 June 2018.