Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on Canvas 47.6 x 48.3 cm

Oil on Canvas 47.6 x 48.3 cm

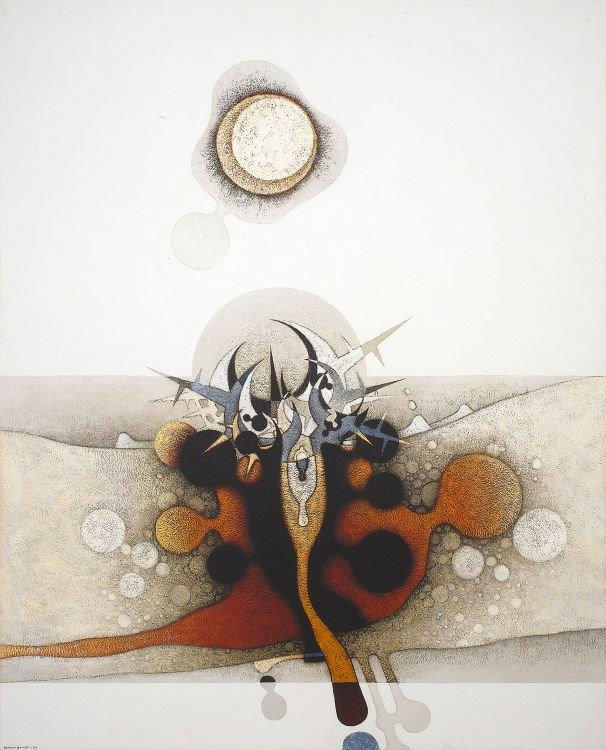

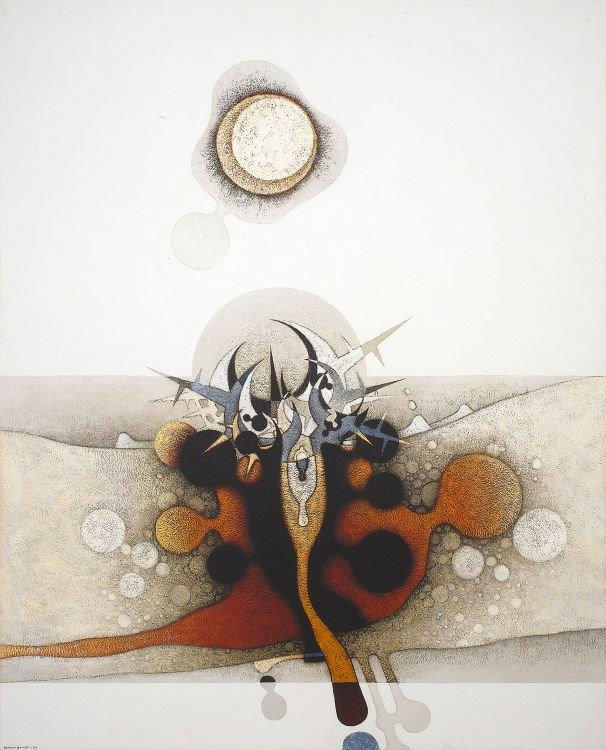

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

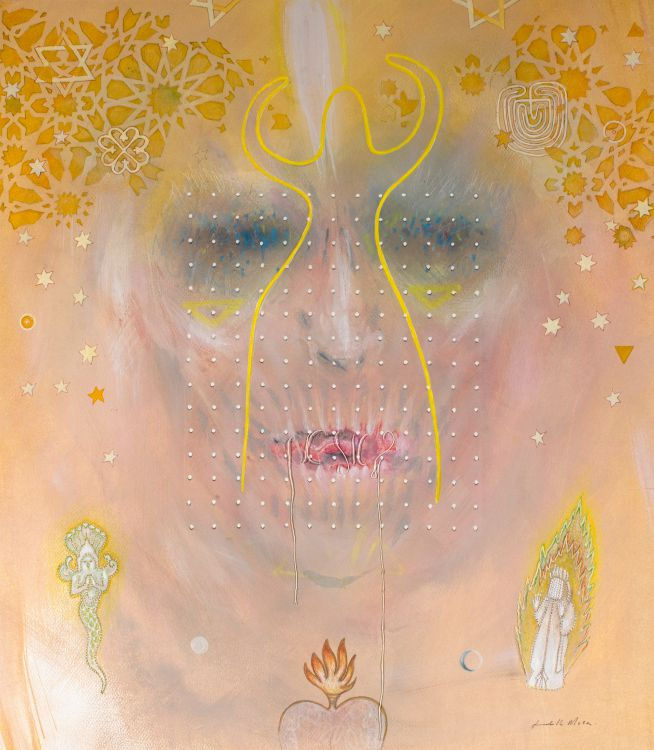

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Dated 1996 Signed lower right, Titled and dated verso, Unframed

Northwest Coast

Inuit Sculpture Artist Unknown

Sedna Soapstone

Sedna Soapstone

High Fired Pottery 27.5 cm x 18.7 cm x 18.7 cm

Acrylic Painted Skull 44 cm x 20 cm

Oil on canvas Signed; Numbered 12-06 76 x 58 cm

Oil on canvas Signed; Numbered 12-06 76 x 58 cm

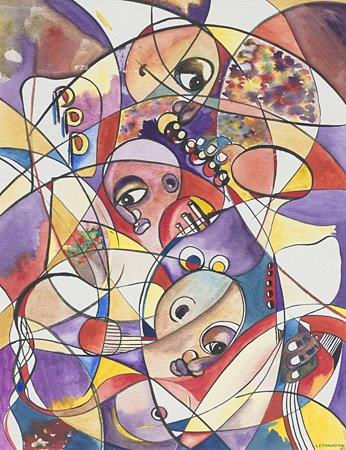

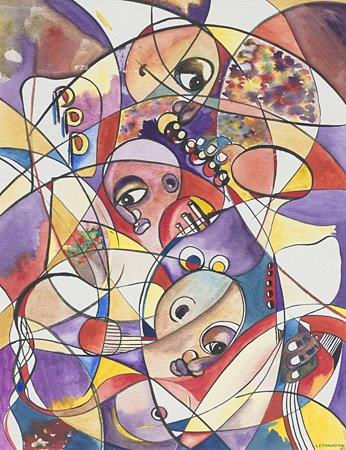

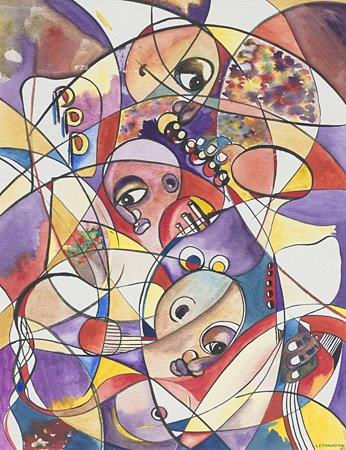

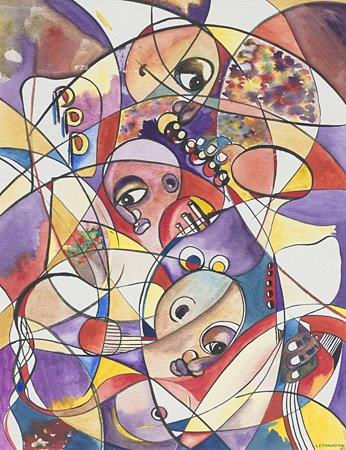

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Oil on canvas 57.2 x 85.5 cm

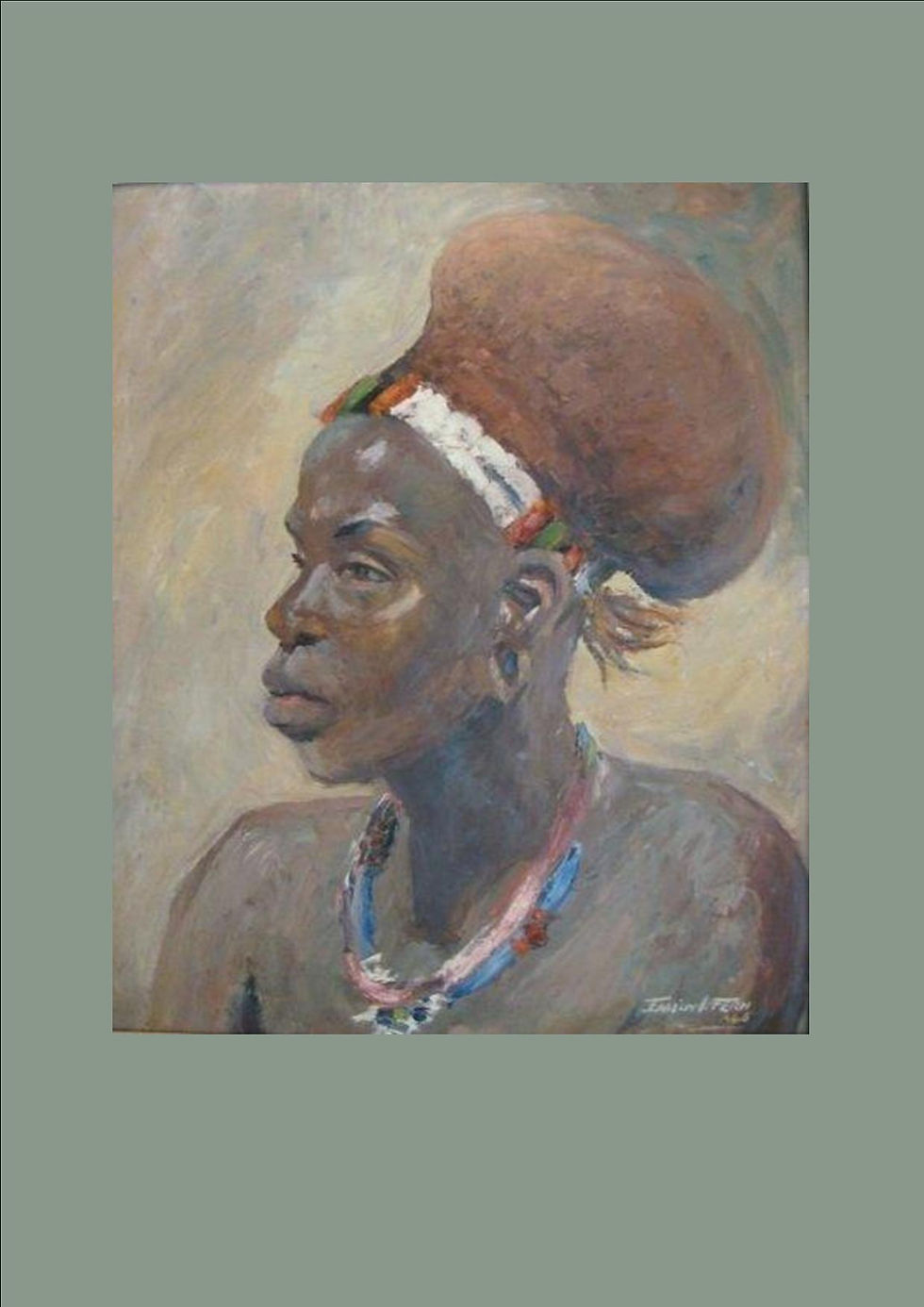

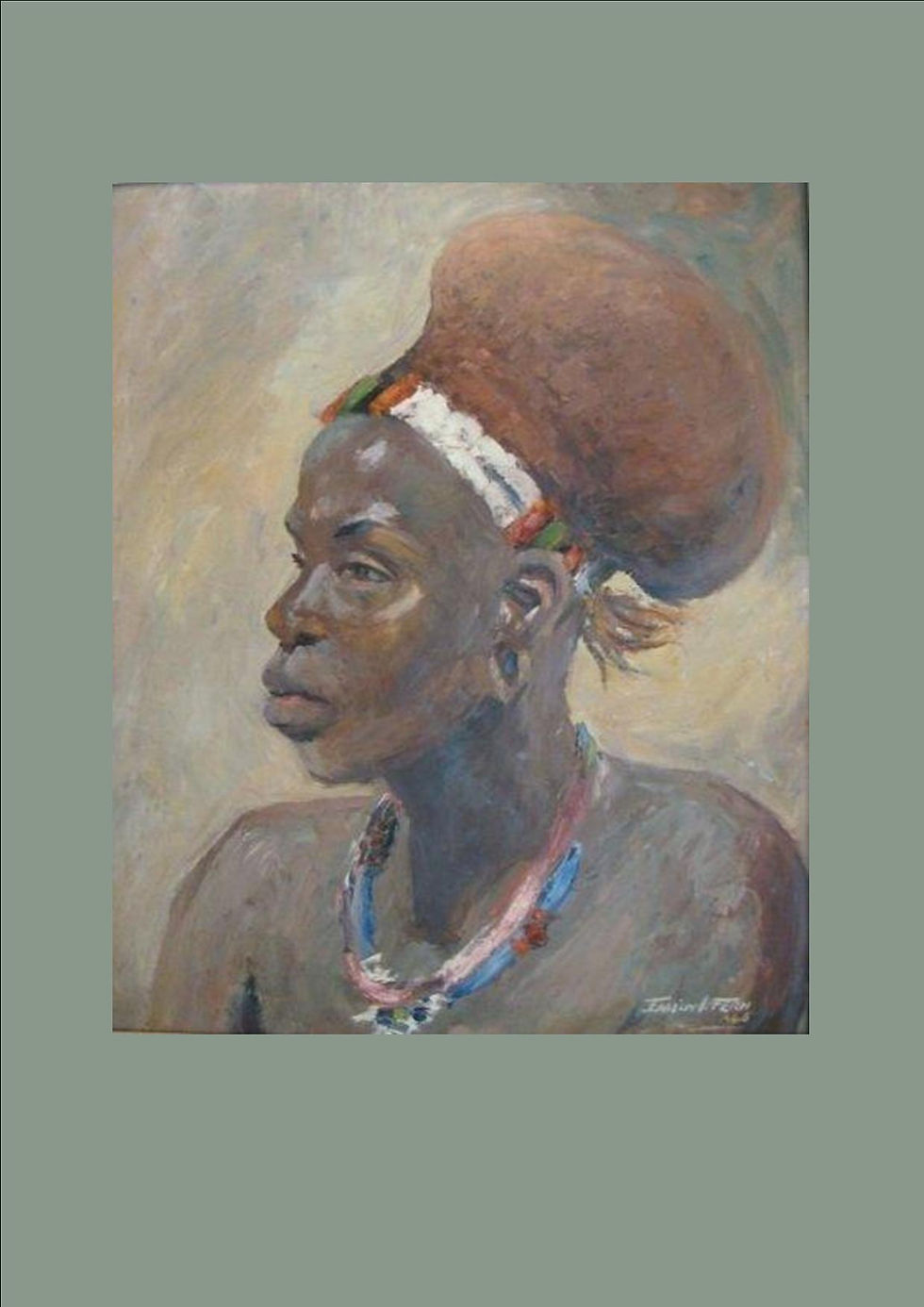

Oil on Board Signed Dated 1962 90 cm x 65 cm

Oil on Board Signed Dated 1962 90 cm x 65 cm

Coloured pencil on paper 24.1 x 18.4 cm 2015

Sunburst Mixed Media on Board 122.5 x 99 cm

Sunburst Mixed Media on Board 122.5 x 99 cm

Bobbie Burgers

Bobbie Burgers is a contemporary Canadian painter. Her lush and Expressionistic depictions of flowers teeter on the verge of abstraction, bursting with bright color and laden with thickly applied, textural paint. “Flowers, to me, are the opposite of still,” the artist has explained. “Changing from minute to minute, they are perfect symbols for life, death, yearning, and beauty. My brushstrokes are layered with my own internal charges, depicting anger, frustration, softness, wanting, and more.” Born in 1973 in Vancouver, Canada, she studied Art History at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. Her work has been exhibited widely at home and abroad, notably including Art Market San Francisco and Equinox Gallery. Today, her works are in the collections of the Berost Corporation in Toronto and the Royal Bank of Canada, among others. Burgers lives and works in Vancouver, Canada.

Bobbie Burgers

Bobbie Burgers is a contemporary Canadian painter. Her lush and Expressionistic depictions of flowers teeter on the verge of abstraction, bursting with bright color and laden with thickly applied, textural paint. “Flowers, to me, are the opposite of still,” the artist has explained. “Changing from minute to minute, they are perfect symbols for life, death, yearning, and beauty. My brushstrokes are layered with my own internal charges, depicting anger, frustration, softness, wanting, and more.” Born in 1973 in Vancouver, Canada, she studied Art History at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. Her work has been exhibited widely at home and abroad, notably including Art Market San Francisco and Equinox Gallery. Today, her works are in the collections of the Berost Corporation in Toronto and the Royal Bank of Canada, among others. Burgers lives and works in Vancouver, Canada.

Oil on canvas Signed 32 x 39 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 32 x 39 cm

Oil on board 44 cm x 45 cm

Oil on board 44 cm x 45 cm

Oil on Canvas Dated 2012 75 cm x 57cm

Oil on Canvas Dated 2012 75 cm x 57cm

Oil Signed .Titled 88 x 120 cm

Oil Signed .Titled 88 x 120 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Acrylic on Board Signed 44 cm x 40 cm

Acrylic on Board Signed 44 cm x 40 cm

Colour Pencil on Paper Signed 16 cm x 11 cm

High Fired Pottery 27.5 cm x 18.7 cm x 18.7 cm

Signed Oil 24 cm x 35 cm

Contemporary South African Art

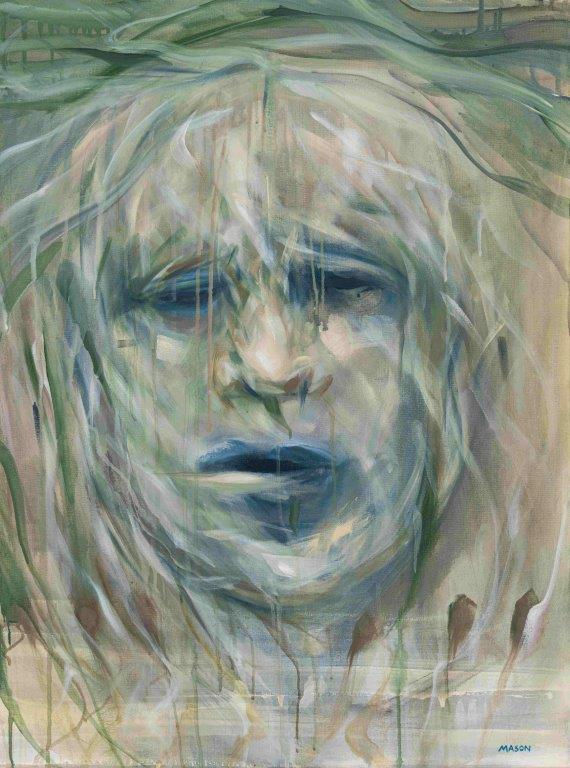

Mason- Attwood, Judith

Article credits to: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judith_Mason

Judith Mason, born Judith Seelander Menge on 10 October 1938 in Pretoria, is a South African artist who has created oil paintings, graphics, mixed media and tapestries, rich in symbolism and mythology, and displaying a rare technical virtuosity.

Judith Mason matriculated at the Pretoria High School for Girls in 1956. She was awarded a BA Degree in Fine Arts at the University of the Witwatersrand in 1960. She taught painting at the University of the Witwatersrand, the University of Pretoria, the Michaelis School of Fine Art in Cape Town, Scuola Lorenzo de' Medici in Florence, Italy from 1989-91 and acted as external examiner for under-graduate and post-graduate degrees at Pretoria, Potchefstroom, Natal, Stellenbosch and Cape Town Universities. Several of Mason's works deal with the atrocities uncovered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[1]

Judith Mason is politically aware and motivated by a strong social conscience. Her work is informed by people, creatures, events and sometimes works of poetry, that have touched or deeply disturbed her. Her images run the gamut from expressionist through representational, humorous and starkly symbolic. The history, mythology and ritual of Christianity and the eastern religions provide a fertile fund of inspiration for her work. Mason feels that formalised theology has destroyed the spiritually-nourishing mythological character of primitive religion.

"I paint in order to make sense of my life, to manipulate various chaotic fragments of information and impulse into some sort of order, through which I can glimpse a hint of meaning. I am an agnostic humanist possessed of religious curiosity who regards making artworks as akin to alchemy. To use inert matter on an inert surface to convey real energy and presence seems to me a magical and privileged way of living out my days". Judith Mason 2004

"Hyaenas like artists, are scavengers prowling on the edge of society. I love hyaenas because of their other-worldly whooping, their ungainliness and their "bad hair" (I share the latter two characteristics). I also regard the animal as a very apt image of the 'id' in opposition to the ego and the super-ego, the monkey on my back. In the three lithographs I have depicted The Muse by Day as a Hyaena in guineafowl's clothing, the spots as disguise or drag to celebrate the gift of mimicry. In the Muse by Night I have concentrated on the animal as far-seeing, seerlike with the coat of spots as shaman's eyes. In Muse Amused I have tried to celebrate a generally despised animal having an existential guffaw." Judith Mason 2006

She has exhibited frequently in South Africa, with works in all the major South African art collections as well as in private and public collections in Europe and the United States. She has held exhibitions in Greece, Italy, The Netherlands, Belgium, Chile, West Germany, Switzerland and the USA.

Her public commissions have included large tapestries in collaboration with Marguerite Stephens and recently, stained-glass window designs for the Great Park Synagogue in Johannesburg. Her first solo exhibition was at Gallery 101, Johannesburg, in 1964 after winning second prize in the U.A.T competition in 1963. Since then she has exhibited regularly in Johannesburg, Cape Town, Pretoria, Stellenbosch and George Goodman Gallery, Chelsea Gallery, Association of Arts Pretoria, Association of Arts Cape Town, Hout Street Gallery, Strydom Gallery, Dorp Street Gallery, Art on Paper, Karen Mackerron Gallery, as well as lithographs, oil paintings and drawings at Ombondi Gallery in New York in 1990. She represented South Africa at the Venice Biennale, 1966, São Paulo Biennale 1973, Brazil, Valparaiso Biennale 1979, Chile and Houston Arts Festival 1980, USA.

Pencil Signed 41 cm x 31 cm

Oil on Canvas Signed 75 cm x 150 cm

Oil and Gold Leaf on Canvas Signed & Dated 74.5 cm x 54.5 cm

Oil on board Signed 99.5 cm x 99.5 cm

Owl Skull Oil and Gouche on Board 29 x 35 cm

2 of 2 Pieces Mixed Media Signed & Titled 29 cm x 28 cm

Oil on Canvas 80 cm x 60 cm Signed

Ink on Paper 53.5 cmx 72 cm Signed

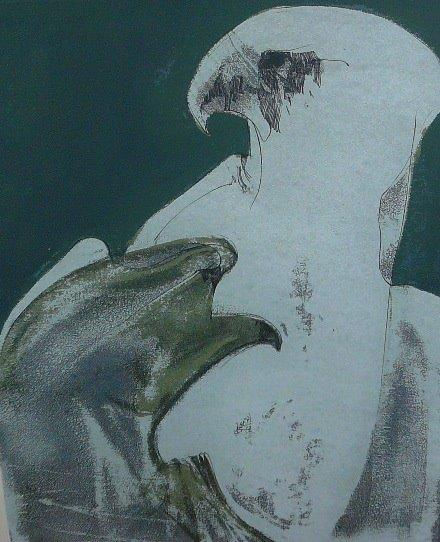

Deadalus and Icarus

The ancient myth of Daedalus and Icarus was first told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses (VIII: 183–235). Icarus’s hubris, resulting in his fall, is so dramatic and spectacular that one often forgets about his father, Daedalus, who seems to be relegated to the background. Daedalus, a skilful craftsman and artist, in all his wisdom and prowess, is best known for the fact that he built the Labyrinth to confine King Minos’s offspring, the Minotaur, on the island of Crete, a deed that resulted in Daedalus and his son being imprisoned in the tower. Daedalus devised the escape plan, configuring two pairs of feather and wax wings, by which the two of them could fly away. But not too close to the sun lest the wax melt, and not too close to the sea lest the feathers get wet. Icarus flew too close to the sun, the wax melted, and he plummeted to his death, but Daedalus flew on and reached the island of Sicily safely.

The hurtling half-figure that dominates much of the picture plane in the present lot is quite ambiguous: it could depict Icarus, with his pair of wings already going up in flames, revealing the bones of his rib cage, or it could depict Daedalus, flying somewhere between sun and sea on an even keel, looking straight ahead, but with an immense sense of sorrow expressed in his eyes and an open mouth from which tears seem to spring in the slipstream of his flight. One is reminded of the WH Auden poem, Musée des Beaux Arts, which refers to the painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c. 1560). The first stanza of the poem reads: “About suffering they were never wrong/The old Masters: how well they understood/Its human position: how it takes place/While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.”

Straight ahead of the Daedalus figure in the present lot is an indistinguishable heap, yet another ambiguity: is it the island of Sicily or the last vestiges of Icarus’s sinking body? Of particular significance in this artwork is the physical gap, a burn mark, or sharp cut, slightly off-centre in the paper, as if Icarus has escaped through that slit into another dimension.

Mason’s work is characterised by her “psychological insight” into the figures she depicts,1 rather than speculative narratives about the subject matter. According to Wilhelm van Rensburg, “it is almost as if Mason pits Dionysus against Apollo in each of her works. As if the emotion and feeling confront the intellect and the rational mind; as if nature ousts reason, or reason displaces chaos.”2

1. Esmé Berman (1983) Art & Artists of South Africa, Cape Town: AA Balkema. Page 276.

2. Wilhelm van Rensburg (2008) Judith Mason: A Prospect of Icons, Johannesburg: Standard Bank Gallery. Page 12.

Lithograph Signed No 56-65 Screenprint 50 cm x 45 cm

Daedalus Icarus Mixed Media on Paper 50 x 70 cm

Drawing 76 cm x 56 cm

Oil on Board Signed Inscribed with Artists name and Title on the Reverse 89 cm x 120.5 cm

Oil and Gold Leaf on Canvas Signed & Dated 74.5 cm x 54.5 cm

Graphite and Collage on Paper 68 cm x 44 cm

Lithograph Signed with Text by Helen Segal 44 cm x 44 cm

Oil on Canvas 80 cm x 60 cm Signed

Lithograph Signed 1973, edition 34-65 49.5 cm x 39 cm

Lithograph Signed 70 cm x 50 cm

Oil on canvas 122 x 91 cm

Mixed media on paper 79.5 cm x 69 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 78 cm x 98 cm

Oil and Gold Leaf on Canvas Signed & Dated 74.5 cm x 54.5 cm

Mixed Media 70 cm x 48 cm

1 of 2 Pieces Mixed Media Signed & Titled 29 cm x 28 cm

Signed Screen Print Dated 93 - No 63-65

A Dante Bestiary - Artists Book Offset lithograph Signed Numbered 54-100 Book 42.5 x 33 x 5.5 cm

Oil on Board Signed 84 cm x 72 cm