Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Acrylic on canvas 30.5 x 30.5 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Oil on Canvas 47.6 x 48.3 cm

Oil on Canvas 47.6 x 48.3 cm

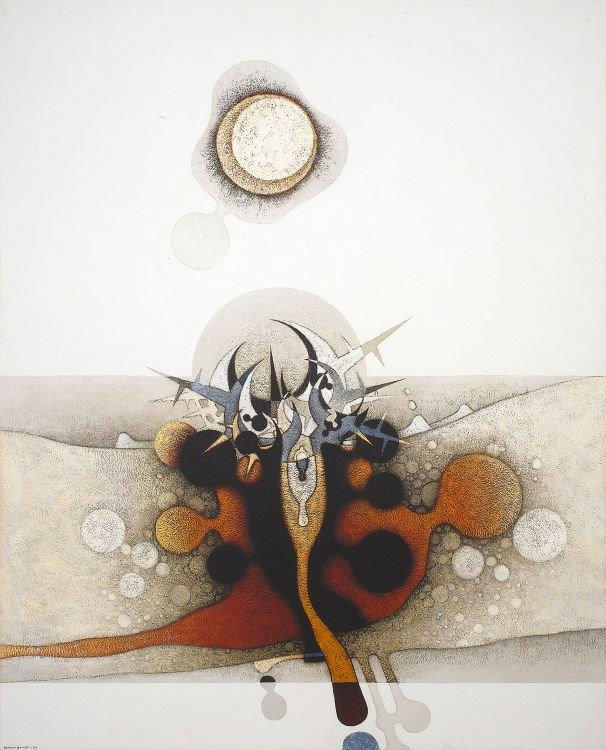

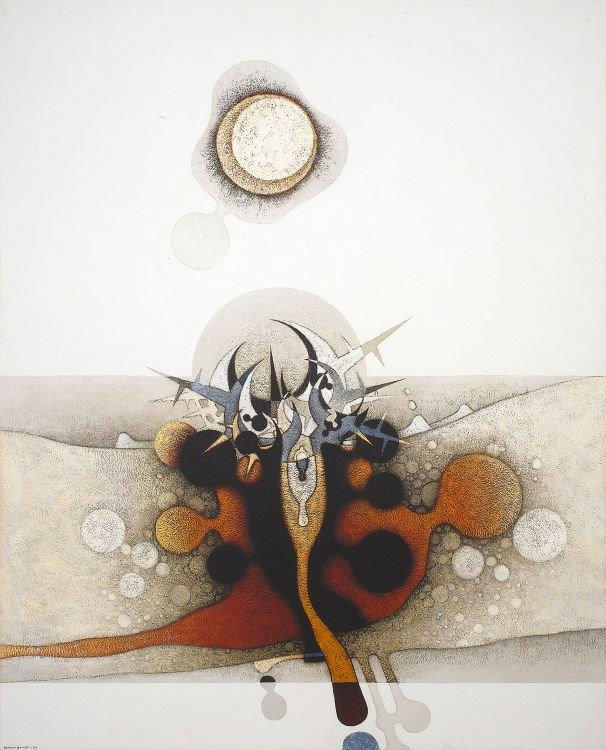

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Gouache on Paper 75 x 55 cm

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Signed lower right; titled and dated verso; unframed

Acrylic on Canvas 91.4 cm x 61 cm Dated 1996 Signed lower right, Titled and dated verso, Unframed

Northwest Coast

Inuit Sculpture Artist Unknown

Sedna Soapstone

Sedna Soapstone

High Fired Pottery 27.5 cm x 18.7 cm x 18.7 cm

Acrylic Painted Skull 44 cm x 20 cm

Oil on canvas Signed; Numbered 12-06 76 x 58 cm

Oil on canvas Signed; Numbered 12-06 76 x 58 cm

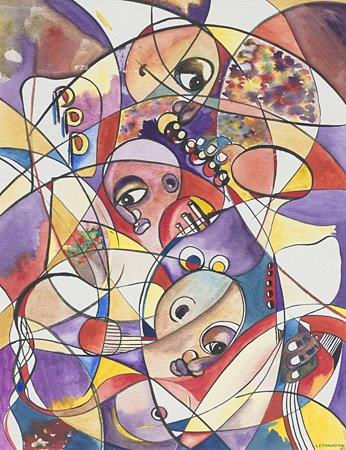

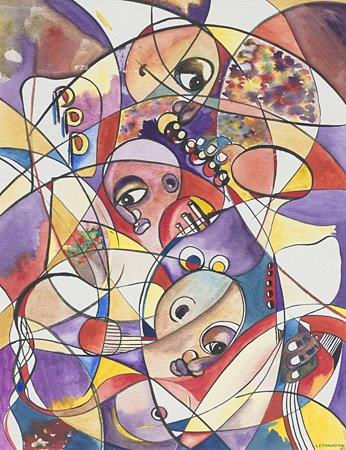

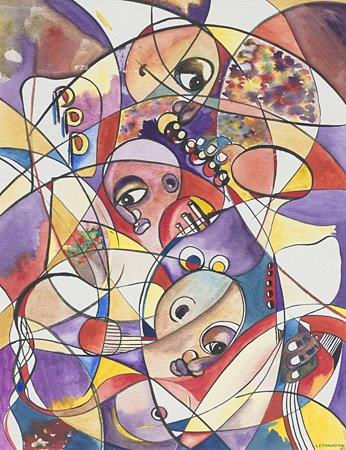

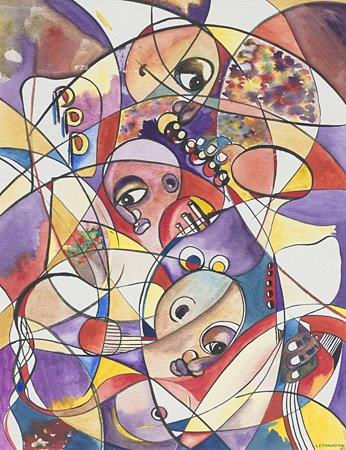

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Watercolor Signed Dated 1993 36 x 28cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Rosewood Tables 78 cm x 150 cm x 54.5 cm

Oil on canvas 57.2 x 85.5 cm

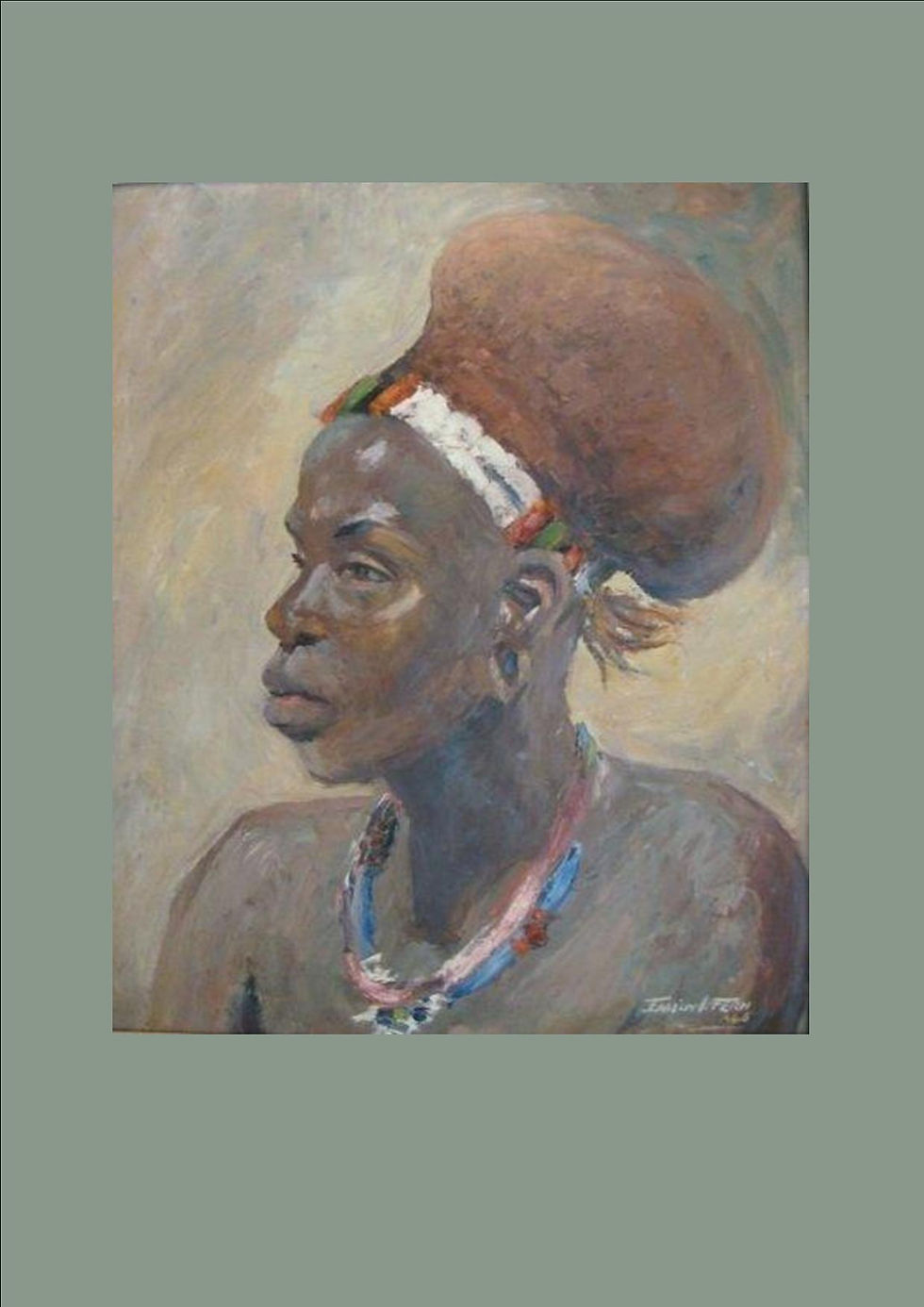

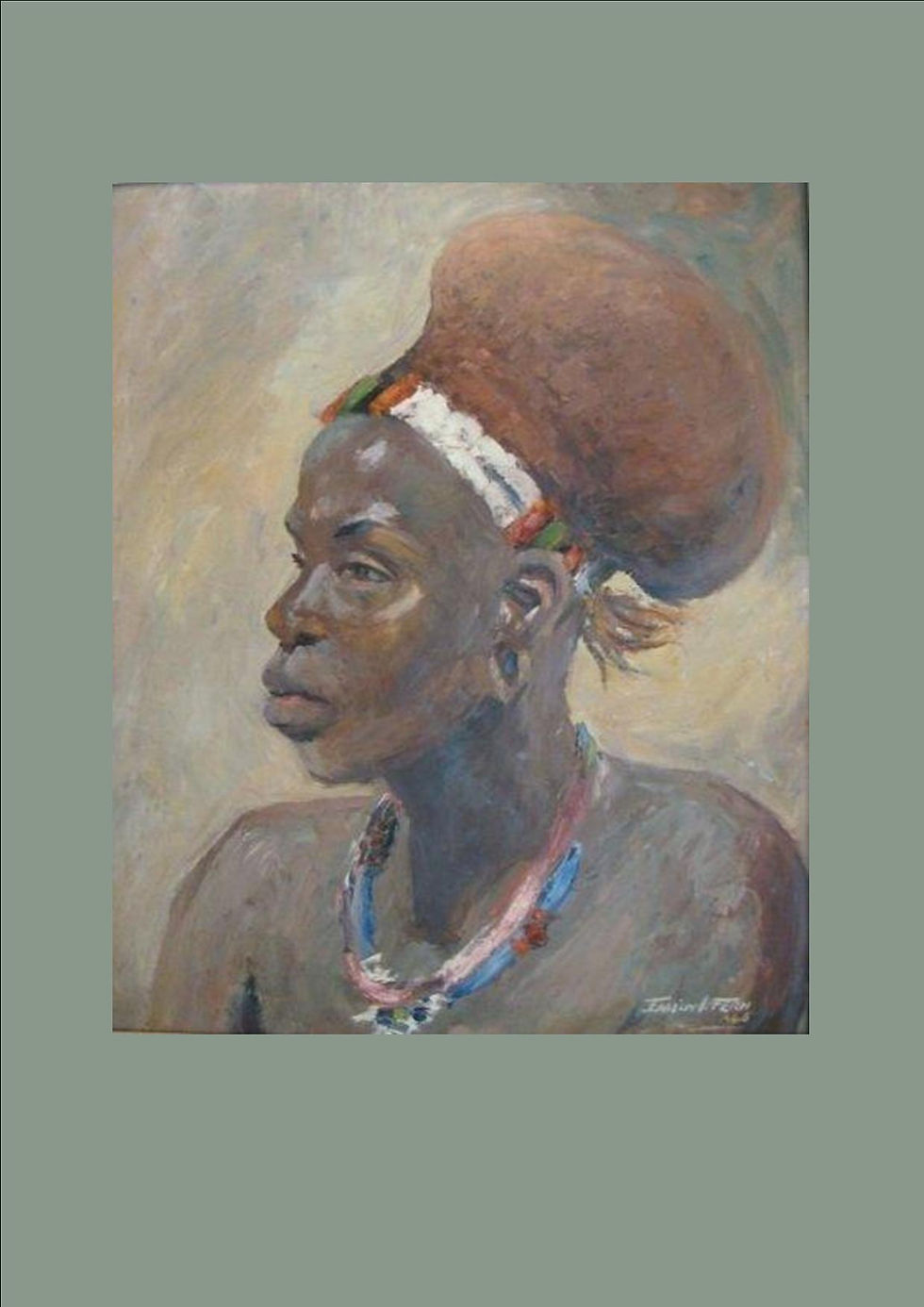

Oil on Board Signed Dated 1962 90 cm x 65 cm

Oil on Board Signed Dated 1962 90 cm x 65 cm

Coloured pencil on paper 24.1 x 18.4 cm 2015

Sunburst Mixed Media on Board 122.5 x 99 cm

Sunburst Mixed Media on Board 122.5 x 99 cm

Bobbie Burgers

Bobbie Burgers is a contemporary Canadian painter. Her lush and Expressionistic depictions of flowers teeter on the verge of abstraction, bursting with bright color and laden with thickly applied, textural paint. “Flowers, to me, are the opposite of still,” the artist has explained. “Changing from minute to minute, they are perfect symbols for life, death, yearning, and beauty. My brushstrokes are layered with my own internal charges, depicting anger, frustration, softness, wanting, and more.” Born in 1973 in Vancouver, Canada, she studied Art History at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. Her work has been exhibited widely at home and abroad, notably including Art Market San Francisco and Equinox Gallery. Today, her works are in the collections of the Berost Corporation in Toronto and the Royal Bank of Canada, among others. Burgers lives and works in Vancouver, Canada.

Bobbie Burgers

Bobbie Burgers is a contemporary Canadian painter. Her lush and Expressionistic depictions of flowers teeter on the verge of abstraction, bursting with bright color and laden with thickly applied, textural paint. “Flowers, to me, are the opposite of still,” the artist has explained. “Changing from minute to minute, they are perfect symbols for life, death, yearning, and beauty. My brushstrokes are layered with my own internal charges, depicting anger, frustration, softness, wanting, and more.” Born in 1973 in Vancouver, Canada, she studied Art History at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. Her work has been exhibited widely at home and abroad, notably including Art Market San Francisco and Equinox Gallery. Today, her works are in the collections of the Berost Corporation in Toronto and the Royal Bank of Canada, among others. Burgers lives and works in Vancouver, Canada.

Oil on canvas Signed 32 x 39 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 32 x 39 cm

Oil on board 44 cm x 45 cm

Oil on board 44 cm x 45 cm

Oil on Canvas Dated 2012 75 cm x 57cm

Oil on Canvas Dated 2012 75 cm x 57cm

Oil Signed .Titled 88 x 120 cm

Oil Signed .Titled 88 x 120 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Mixed Media and Collage on canvas Signed Dated 16 163 cm x 160 cm

Oil on canvas Signed 53 x 106 cm

Acrylic on Board Signed 44 cm x 40 cm

Acrylic on Board Signed 44 cm x 40 cm

Colour Pencil on Paper Signed 16 cm x 11 cm

High Fired Pottery 27.5 cm x 18.7 cm x 18.7 cm

Signed Oil 24 cm x 35 cm

Contemporary South African Art

Heath, Jack

A.R.C.A (1915 – 1969)

John Charles Wood Heath (Jack) was born in Cannock in Staffordshire on 22nd May 1915, into what he always proudly referred to as a working class family, although, as his father was a colliery clerk rather than a labourer, it might perhaps be more accurate to speak of a lower or lower-middle class background. Whatever the niceties of sociological definition, it was a background of which he was immensely proud.

His father rose to become a sub-Postmaster while Jack was a boy, and the family lived above the shop on the corner of two long rows of typical late 19th Century two-up two-down terraced houses in Aston in Birmingham, most of which lacked indoor plumbing. Jack attended the Acock’s Green and Aston Elementary Schools, and in 1926 won a Scholarship to the Handsworth Grammar School, which was established in 1862. It still exists in its original buildings, the last of the great Birmingham Grammar Schools to do so. Birmingham had an excellent system of grammar schools, which were established to serve the academically bright sons of the working and lower middle class living within the area, and which were entered by examination, purely on merit, at the age of eleven. They provided an education equivalent to the public schools of the wealthy.

In 1931 Jack matriculated and achieved a distinction in history, a subject which remained a great interest throughout his life. For the Higher School Certificate in 1932 he studied English Literature, History and Art.

He won a scholarship to the Birmingham School of Arts and Crafts in 1932, where in 1934 he won the Drawing Prize and in 1935 the Louisa Ann Ryland Travelling Scholarship.

A further scholarship took him to the Royal College of Art in London, where he enrolled in the Engraving School under Malcolm Osborne R.A., C.B.E. He won the British Institute Empire Scholarship in Engraving, which was open to the entire Commonwealth, in 1938. He won both the Drawing Prize and a Fourth Year Extension Scholarship in 1939, but he was unable to take up the latter as he volunteered for service in the army immediately upon the outbreak of war.

Jack was a fine athlete. He was the Midlands Schools Javelin Champion from 1929 to 1932, the British Junior and Midlands Senior Champion in 1932, and he participated in the Empire Games at White City Stadium in 1934. He was invited to the trials for the Berlin Olympics, but injury intervened.

During the War he rose from private in the Coldstream Guards to Staff Officer (Camouflage). He saw action in Italy in 1943 and was injured on Queen’s Beach in the Normandy Landing on 6th June 1944, and evacuated. Some of the drawings he made of his experience of the historic landing were bought by the British Government and are part of the collections of the Imperial War Museum in London and the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich.

During his army career he was responsible, inter alia, for Coastal Defences in Orkney and Shetland (defending the Fleet Anchorage), the Dover Coast, Kent, Essex and the Thames Estuary. He was Staff Officer (Camouflage) to the 6th A.A. Division, the 2nd A.A. Corps, the 11th Overseas Training Brigade, the 15th Army Group H.Q., and the 21st Army Group H.Q. In his postings he was involved in the training of all arms in Camouflage and Deception and the establishment of Schools of Camouflage.

His last posting was to the School of Naval Air Warfare in St. Merryn, Cornwall, where he was responsible for the establishment of a School for senior pilots of the Fleet Air Arm, for training in camouflage methods, aerial photographic interpretation and close army support.

He was demobilized in 1946, awarded the King’s Medal for Disabled Servicemen, and granted the honorary title of Captain.

Jack married Jane Tully Parminter, his companion since they met on their third day at the Birmingham School of Arts and Crafts in 1932, on 18th January 1940.

The diversion of seven years of war service, appalling though it was, was not entirely without value for Jack’s subsequent career. Throughout most of this time he was establishing schools of camouflage and training all arms including very senior officers, and this experience was of immense value when he renewed his career in art in South Africa in the second half of 1946, by which time he was entirely confident in his powers of both organisation and instruction.

Furthermore, the long years of familiarity with the practicalities of the visual art of camouflage, the aerial photography and the model-making for the coastal defences had a clear and fascinating influence on his subsequent career as an artist, up to and including his most abstract work.

In mid-1946, after applying for posts in Britain and the Commonwealth, he took up a post at Rhodes University College as Lecturer in Painting and Drawing. But it appears he was head-hunted by the Port Elizabeth Technical College, and he was appointed Head of the Art School in 1947.

His years in Port Elizabeth, from 1947 to 1952, were very fruitful. The tangible evidence of his success at the Technical College included the increase in the number of students from about 400 in 1947 to about 750 in 1952, and the winning of the Art School Trophy in the South African National Eisteddfod for five successive years. Anthony Delius wrote “The progress of the Art Department at the Technical College was a matter of common favourable comment………an achievement in a city where the arts are regarded with some suspicion”. Mr A. Gregory, the Acting Principle of the Technical College in 1952, wrote “….there is also the less tangible but still quite definite point that he has placed the Art School “on the map” as far as this city of Port Elizabeth is concerned; there is a general appreciation of the fact that it is a progressive and culturally important institution.”

Jack fought for financial aid for poor students and for scholarships for the gifted, and he introduced classes for the Coloured and Chinese communities of the city.

In addition to his vigorous teaching and organizational duties he drew regular political cartoons and humorous drawings for the Saturday Post. (In a short article in the paper in 1947, in which he was introduced to the readers, it was written “It is difficult to tell how old Jack Heath is; a rugged exterior, a broad moustache and a slightly balding head will make calculation more difficult. But the heart within is impishly critical, the mind alert and the judgment sharp”.) Together with Jane he undertook several mural commissions, he gave lecture series for the public, and of course he continued to make his own work.

Jack was appointed to the Chair of Fine Art at Natal University College in Pietermaritzburg in January 1953. The department, by all accounts, was moribund prior to his arrival, with grey teachers teaching grey painting, and with dismal library holdings. Harold Strachan, who had been a student in these sombre days, wrote in the Natal Witness in July 2009 “It was darem a dismal place. So you will understand my surprise, nay delight, when I returned to this cemetery a couple of years later to teach and lo! The place was one blaze of full-colour oil paintings, and big, man, like the new professor”.

Jack, with his well-honed organisational abilities, teaching skills and enormous conviction and vigour, transformed the Department (together with Jane, who was first employed in 1954) into a place of great vitality. He introduced Art History as a serious endeavour for the first time, hugely enlarged the library holdings, and introduced Sculpture as a major. Both he and Jane, influenced by their training at the Birmingham School, introduced the mural as a serious area of study for the full Honours year, and several fine murals still grace the campus.

Fine Art, unsurprisingly, was not taken very seriously by the University when Jack arrived, and was house in a motley selection of Nissen huts and the top floor of the old library. It expanded to include an abandoned science laboratory and a dungeon (for sculpture). Jack fought a protracted battle for a dedicated building, and finally won when Fine Art moved into its present building in 1964, although courtesy the University it was the cheapest building per-square-foot on the campus, and the powers changed the aspect of the building so that the planned South light, perfect for painters, was lost, this latter to protect part of a hockey-field. (Nonetheless, the new building was originally a place full of light, with open courtyards for work and leisure. It is much changed since Jack’s death, the courtyards covered, the light and air diminished).

Throughout this time Jack continued to study on his own account as well as that of his students. He was a voracious reader of, inter alia, history, biography, comparative religion and of course art. He was a serious student of the Quattrocento, with a deep interest in the science of picture-making of the period. He applied his knowledge in the great series of religious works which he commenced in 1956, and this knowledge is manifest up to his final large abstracts of 1966 to 1969.

Jack died suddenly of a cerebral haemorrhage on 16th June 1969. In his obituary Derek Leigh wrote “He was a good professor, a good friend and a good colleague. Of all his qualities I would list his abundant generosity first. He would always go out of his way, as unobtrusively as possible, to help anyone, not only students, who were in trouble or need. He had the generosity to have a large measure of human feeling, sympathy and humility. He was no lover of verbosity or sham and his good share of common sense gave rise to a very robust sense of humour. He was so burly and seemed so formidably bluff, but in reality he was a shy, kindly man.”

Professor Alfred Rooks wrote “Behind the military exterior of an officer and a gentleman was hidden quite a different, highly attractive personality. There was the sensitive aesthete and artist of no mean calibre, a deep thinker……and a very honest and humble man. (His) works gave expression to all that he was, to the previously mentioned characteristics and to many more, likewise endearing: his humour, his sense of pity, his affection for his fellows, and his sense of justice. Fine artist that he was, he never displayed arrogance, dogmatism or eccentricity. There was no pathetic craving for self-expression disguised as wisdom.... To students and colleagues he will always remain an example to follow and imitate in search of true humanity and real virtues.”

Port Elizabeth Street Scene Oil on Board 1952 42 cm x 93 cm

Mixed Media on Paper 1965 50 cm x 68 cm

Oil on Board Signed Dated 1959 121 cm x 168 cm

Crushed Glass, and Oil on Board Signed and Dated 1962 Title Inscribed on Reverse 121.5 cm x 244 cm

Not Far Away Indian Ink Gouache and wax crayon paper

Encaustic and oil on board 120.5 x 181 cm